Rob lA Frenais

Interrogating Reality - '80s style

play video >

talk: duration 60 mins; video documentation above 58 mins 54 secs

Writer and curator Rob La Frenais gave this talk as part of the Festival’s

Early Bird programme of post breakfast events.

From the original Festival website:

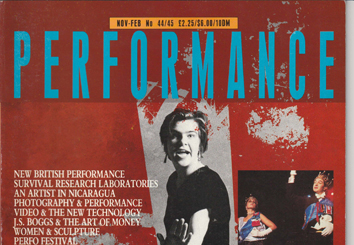

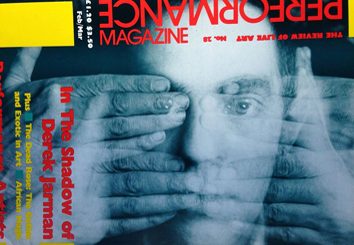

When I founded Performance Magazine in 1979, it was clear there was a gap in the documentation of new forms of art that veered away from the object and away from theatre. Yet Performance Magazine, though regularly featuring profiles of ‘classical’ performance art figures – for example the British performance art duo The Kipper Kids appeared in its first issue before going on to feature interviews with artists such as John Cage and Joseph Beuys – was also inspired by the Nicolas Roeg/Donald Cammell movie by the same name, Performance,and continued to reflect themes from that movie through its 13-year life. That film, in its interaction and reality exchange between the rock star fop, Jagger and the gangster Turner, based on the Borges theme of the doppelganger from the story Tlon Iqbar, Orbis Tertius, set a theme of interrogating reality that was soon to become the magazine’s hallmark.

The gauntlet was thrown down early by the director of the theatre group The Phantom Captain (1970), Neil Hornick, in his cover interview with the iconic comedian Charlie Drake. It continued with a ‘refocussing’ of West End theatre, reaching its ultimate provocation in an interview with Fiona Richmond who was at that time appearing in the bedroom farce of the period: Wot, No Pyjamas?

In State Performance, the ‘fairytale’ Royal Wedding for Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer was given the full Performance treatment with articles by Lynn MacRitchie comparing the wedding to that of the Yorkshire Ripper, by myself on the performative power of heraldry, and with a specially commissioned performance for the cover by performance duo Marty St James and Anne Wilson, who conducted a mock wedding on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral. Of course life always outperforms art, so had we known when planning our special issue that the Prince and his long-time mistress had been part of a larger, cynical plot to find a nineteen year old virgin commoner to renew a flagging inbred monarchy (and then, according to popular myth, to assassinate), we might have revised our analysis more along the lines of conspiracy theory.

Long before Tracey Emin started her artistic practice, we were re-interpreting bedding as art, and when the late Steve Rogers joined the team, there would always be a feature on events such as Crufts Dog show, the Ideal Home exhibition and the Earls Court Boat Show. There would sometimes be a more serious thematic to this, and the idea of performance as a fluid gesture started to emerge as we engaged more and more in performance as process, proceeding to land art and journeys by horse and cart. A special issue on performance journeys for example, was inspired by a project by artist Johannes Cornellison in which he circumnagivated the world, documenting points at which the equator was marked.’Art on the Run’ was another issue where to review a single performance by Bath’s Natural Theatre company over a period of three weeks during the Lands End to John O’Groats bike ride, I, as editor, rode a bicycle all the way, taking notes.

Art interrogating reality became seriously analysed in a special issue we did on artists becoming totally immersed in other professions or activities such as ballroom dancing and deep sea diving. The late Steve Cripps, who took performance pyrotechnics to their ultimate conclusion, was interviewed about his membership of the Fire Brigade. After having the Fire Brigade called out to several of his performances, this was the ultimate ironic choice. For Cripps it was also a chance to learn more “to pick up something about the field he worked in: smoke, fire, bangs and flashes.” But something like the Fire Brigade is bound to change you; it is not something you could just slip in and out of, as Cripps stated, “They wanted to know I wasn’t just going to just stay a few months and write a book about it”. An everyday experience of the great show that occurs when a fire engine comes tearing round the streets with firemen hanging off the sides suggests that in their own way, firemen are no strangers to performance.

Writing in 1983, I go on to ask, ‘what is the actual difference between an artist who becomes a fireman and a fireman who, say, potters around a bit with paints in his spare time?’ – a question which could be posed about the artists who want to become astronauts or nuclear engineers and the astronauts and nuclear engineers who want to become artists. For Cripps, his life as an artist had already changed: At first he “just wanted to know if you could do it” but now the practice of stretching himself to the limits, fighting fires and actually saving lives seems to have become more important. And the future? I’m waiting to be called out to an art gallery...

From: Ubiquity and Fluidity Chapter 3 ‘Interrogating reality’, Rob La Frenais 2007

Interrogating Reality – ’80s style

Writer and curator Rob Le Frenais gave this talk as part of the Festival’s Early Bird programme.WATCH VIDEO

From the original Festival website: When I founded Performance Magazine in 1979, it was clear there was a gap in the documentation of new forms of art that veered away from the object and away from theatre. Yet Performance Magazine, though regularly featuring profiles of ‘classical’ performance art figures – for example the British performance art duo The Kipper Kids appeared in its first issue before going on to feature interviews with artists such as John Cage and Joseph Beuys – was also inspired by the Nicolas Roeg/Donald Cammell movie by the same name, Performance, and continued to reflect themes from that movie through its 13-year life. That film, in its interaction and reality exchange between the rock star fop, Jagger and the gangster Turner, based on the Borges theme of the doppelganger from the story Tlon Iqbar, Orbis Tertius, set a theme of interrogating reality that was soon to become the magazine’s hallmark.

The gauntlet was thrown down early by the director of the theatre group The Phantom Captain (1970), Neil Hornick, in his cover interview with the iconic comedian Charlie Drake. It continued with a ‘refocussing’ of West End theatre, reaching its ultimate provocation in an interview with Fiona Richmond who was at that time appearing in the bedroom farce of the period: Wot, No Pyjamas?

In State Performance, the ‘fairytale’ Royal Wedding for Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer was given the full Performance treatment with articles by Lynn MacRitchie comparing the wedding to that of the Yorkshire Ripper, by myself on the performative power of heraldry, and with a specially commissioned performance for the cover by performance duo Marty St James and Anne Wilson, who conducted a mock wedding on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral. Of course life always outperforms art, so had we known when planning our special issue that the Prince and his long-time mistress had been part of a larger, cynical plot to find a nineteen year old virgin commoner to renew a flagging inbred monarchy (and then, according to popular myth, to assassinate), we might have revised our analysis more along the lines of conspiracy theory.

Long before Tracey Emin started her artistic practice, we were re-interpreting bedding as art, and when the late Steve Rogers joined the team, there would always be a feature on events such as Crufts Dog show, the Ideal Home exhibition and the Earls Court Boat Show. There would sometimes be a more serious thematic to this, and the idea of performance as a fluid gesture started to emerge as we engaged more and more in performance as process, proceeding to land art and journeys by horse and cart. A special issue on performance journeys for example, was inspired by a project by artist Johannes Cornellison in which he circumnagivated the world, documenting points at which the equator was marked. ‘Art on the Run’ was another issue where to review a single performance by Bath’s Natural Theatre company over a period of three weeks during the Lands End to John O’ Groats bike ride, I, as editor, rode a bicycle all the way, taking notes.

Art interrogating reality became seriously analysed in a special issue we did on artists becoming totally immersed in other professions or activities such as ballroom dancing and deep sea diving. The late Steve Cripps, who took performance pyrotechnics to their ultimate conclusion, was interviewed about his membership of the Fire Brigade. After having the Fire Brigade called out to several of his performances, this was the ultimate ironic choice. For Cripps it was also a chance to learn more – to pick up something about the field he worked in: smoke, fire, bangs and flashes. But something like the Fire Brigade is bound to change you; it is not something you could just slip in and out of, as Cripps stated, ‘They wanted to know I wasn’t just going to just stay a few months and write a book about it’. An everyday experience of the great show that occurs when a fire engine comes tearing round the streets with firemen hanging off the sides suggests that in their own way, firemen are no strangers to performance.

Writing in 1983, I go on to ask, ‘what is the actual difference between an artist who becomes a fireman and a fireman who, say, potters around a bit with paints in his spare time?’ – a question which could be posed about the artists who want to become astronauts or nuclear engineers and the astronauts and nuclear engineers who want to become artists. For Cripps, his life as an artist had already changed: ‘At first he “just wanted to know if you could do it” but now the practice of stretching himself to the limits, fighting fires and actually saving lives seems to have become more important. And the future? “I’m waiting to be called out to an art gallery”.

From: Ubiquity and Fluidity Chapter 3 ‘Interrogating reality’ Rob La Frenais 2007

roblafrenais.info

When I founded Performance Magazine in 1979, it was clear there was a gap in the documentation of new forms of art that veered away from the object and away from theatre. Yet Performance Magazine, though regularly featuring profiles of ‘classical’ performance art figures – for example the British performance art duo The Kipper Kids appeared in its first issue before going on to feature interviews with artists such as John Cage and Joseph Beuys – was also inspired by the Nicolas Roeg/Donald Cammell movie by the same name, Performance, and continued to reflect themes from that movie through its 13-year life. That film, in its interaction and reality exchange between the rock star fop, Jagger and the gangster Turner, based on the Borges theme of the doppelganger from the story Tlon Iqbar, Orbis Tertius, set a theme of interrogating reality that was soon to become the magazine’s hallmark.

The gauntlet was thrown down early by the director of the theatre group The Phantom Captain (1970), Neil Hornick, in his cover interview with the iconic comedian Charlie Drake. It continued with a ‘refocussing’ of West End theatre, reaching its ultimate provocation in an interview with Fiona Richmond who was at that time appearing in the bedroom farce of the period: Wot, No Pyjamas?

In State Performance, the ‘fairytale’ Royal Wedding for Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer was given the full Performance treatment with articles by Lynn MacRitchie comparing the wedding to that of the Yorkshire Ripper, by myself on the performative power of heraldry, and with a specially commissioned performance for the cover by performance duo Marty St James and Anne Wilson, who conducted a mock wedding on the steps of St Paul’s Cathedral. Of course life always outperforms art, so had we known when planning our special issue that the Prince and his long-time mistress had been part of a larger, cynical plot to find a nineteen year old virgin commoner to renew a flagging inbred monarchy (and then, according to popular myth, to assassinate), we might have revised our analysis more along the lines of conspiracy theory.

Long before Tracey Emin started her artistic practice, we were re-interpreting bedding as art, and when the late Steve Rogers joined the team, there would always be a feature on events such as Crufts Dog show, the Ideal Home exhibition and the Earls Court Boat Show. There would sometimes be a more serious thematic to this, and the idea of performance as a fluid gesture started to emerge as we engaged more and more in performance as process, proceeding to land art and journeys by horse and cart. A special issue on performance journeys for example, was inspired by a project by artist Johannes Cornellison in which he circumnagivated the world, documenting points at which the equator was marked. ‘Art on the Run’ was another issue where to review a single performance by Bath’s Natural Theatre company over a period of three weeks during the Lands End to John O’ Groats bike ride, I, as editor, rode a bicycle all the way, taking notes.

Art interrogating reality became seriously analysed in a special issue we did on artists becoming totally immersed in other professions or activities such as ballroom dancing and deep sea diving. The late Steve Cripps, who took performance pyrotechnics to their ultimate conclusion, was interviewed about his membership of the Fire Brigade. After having the Fire Brigade called out to several of his performances, this was the ultimate ironic choice. For Cripps it was also a chance to learn more – to pick up something about the field he worked in: smoke, fire, bangs and flashes. But something like the Fire Brigade is bound to change you; it is not something you could just slip in and out of, as Cripps stated, ‘They wanted to know I wasn’t just going to just stay a few months and write a book about it’. An everyday experience of the great show that occurs when a fire engine comes tearing round the streets with firemen hanging off the sides suggests that in their own way, firemen are no strangers to performance.

Writing in 1983, I go on to ask, ‘what is the actual difference between an artist who becomes a fireman and a fireman who, say, potters around a bit with paints in his spare time?’ – a question which could be posed about the artists who want to become astronauts or nuclear engineers and the astronauts and nuclear engineers who want to become artists. For Cripps, his life as an artist had already changed: ‘At first he “just wanted to know if you could do it” but now the practice of stretching himself to the limits, fighting fires and actually saving lives seems to have become more important. And the future? “I’m waiting to be called out to an art gallery”.

From: Ubiquity and Fluidity Chapter 3 ‘Interrogating reality’ Rob La Frenais 2007

roblafrenais.info